December 25, 2011 – From The Sunday Albuquerque Journal“ Copyright © 2011 Albuquerque Journal

SILENT NIGHT, Holy Night, Sisters Mark Christmas, and Life, in Quiet Ways by Olivier Uytterbrouck, Journal Staff Writer

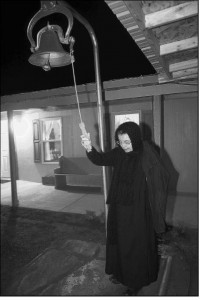

BLANCO: “Christmas is a time of silence at the Monastery of Our Lady of the Desert. The silence here is so profound it seems to amplify even tiny sounds, such as a whispered psalm or the clang of a bell that calls the sisters to prayer seven times each day. Silence doesn’t mean no noise, said Sister Julianne Allen, 80, one of seven sisters who compose the small Benedictine community about 35 miles east of Farmington. You can have exterior silence and be too busy in your head to hear anything. More important than silence is a quietness within.

I think that’s what Christmas is about: to find that silence, because Christ comes in silence, she said. Christmas is really the time to be still so you can hear the gentle voice of God.

The silence and predawn darkness here have a gravity that city dwellers rarely experience.

Mother Benedicta Serna, the community mother superior, stood in the freezing air before sunrise and pointed to the distant headlights of a car passing on U.S. 64, a mile north of the monastery“ far enough away that the engine was inaudible. There is the world passing by out there, she said.

Our Lady of the Desert is a silent religious order, meaning the sisters refrain from speaking at certain times, such as during meals. At other times, the monastery rings with talking and laughter or the clatter of pans and dishes as the sisters prepare meals.

The sisters day will have started hours before most New Mexicans begin stirring on Christmas morning.

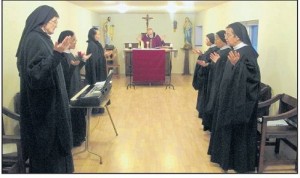

They rise at 4 a.m. every day and gather in the chapel a half-hour later to sing hymns, read psalms and pray.

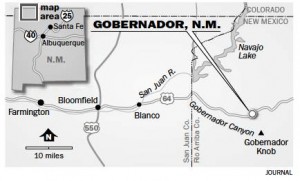

The monastery is housed in a clutch of refurbished manufactured homes at the end of a dirt road. Earlier this month, workers hauled a new mobile home to the site to serve as guest quarters.

The sisters plan to eventually build a new monastery atop a high mesa nearby and use the current facilities to sponsor retreats and provide income for the community.

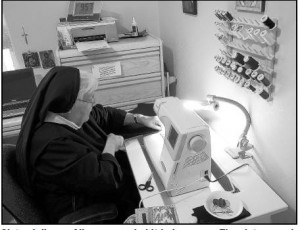

For now, the monastery remains largely dependent on donations of money, work and food. The sisters set aside a four-hour work period each day for tasks such as sewing, cleaning and making crafts for sale.

To the south looms 7,000-foot Gobernador Knob, named for the Navajo deity Changing Woman.

For the women of Our Lady of the Desert, recent years have brought many changes.

In 2008, the nuns abandoned a comfortable home in Abiquiu where they had lived since 1997 under the protection of the Monastery of Christ in the Desert, a 37-year-old monastic community for men.

“Our life was good at Christ in the Desert, but we did own our own property,” Sister Mary Fisher said. We didn’t have a say in any decisions. Nobody knew we were there. We were hidden away.

First, they moved to temporary quarters at St. Rose of Lima parish in Blanco, then in 2009 to their present home on 40 acres of donated land. In that time, the number of sisters dwindled from 11 to seven. They range in age from 44 to 80.

It was very difficult, Fisher recalled. We didn’t have any money. We didn’t know what we were in for. The sisters who left for other communities were troubled by the uncertainty, she said. Some of the sisters couldn’t handle it.

Evidence of Christmas is muted at Our Lady of the Desert during the Advent season. The sisters place a holly wreath in the chapel during the weeks of Advent and set up a nativity scene on Christmas Eve. But their daily cycle of prayer and work changes little.

Traditions such as Christmas trees, farolitos and caroling were absent at the first Christmas, and so they will be today at Our Lady of the Desert.

Our silence of Christmas is like the silence of Our Savior being born in the stillness and quietness of the manger, Sister Kateri Lovato explained in an email. It is so simple, it becomes hard to grasp.” This article appeared on page A1 of the Albuquerque Journal