Saint Benedict of Nursia (c. 480-547) lived in central Italy during the fifth and sixth centuries. After some experience of life as a hermit, he founded monasteries at Subiaco and later at Monte Cassino. Like other monastic founders of that time, he composed for these communities a rule for the monastic life that depended in large part on earlier sources but also benefited from his own wisdom and experience. With genuine humility he called it a minimum Rule for beginners and hoped that it would lead faithful disciples to the loftier heights of doctrine and virtue of other monastic authorities. He wrote nothing else. His contemporaries took no note of him, at least not enough to cause him to be mentioned in any other document of his time. What little we do know of his life, and the miracles attributed to him, is found in Book II of the sixth-century Dialogues of Pope Saint Gregory the Great, which the pope says were based on the testimony of contemporaries and near contemporaries of the recently deceased saint.

One is drawn to Saint Francis by the stories told about him, which are know to Franciscan and non-Franciscan alike; how he embraced the leper, stripped himself of his garments, rebuilt the ruined church, gathered disciples, journeyed to the Holy Land, and received the stigmata. However, touching they may be, the stories are not how Saint Benedict is known. The miracles which so impressed Saint Gregory may well seem to modern readers to be quaint relics of a more credulous age, a didactic hagiography foreign to our tastes. Gregory himself explains why one is, nonetheless, drawn to Benedict.

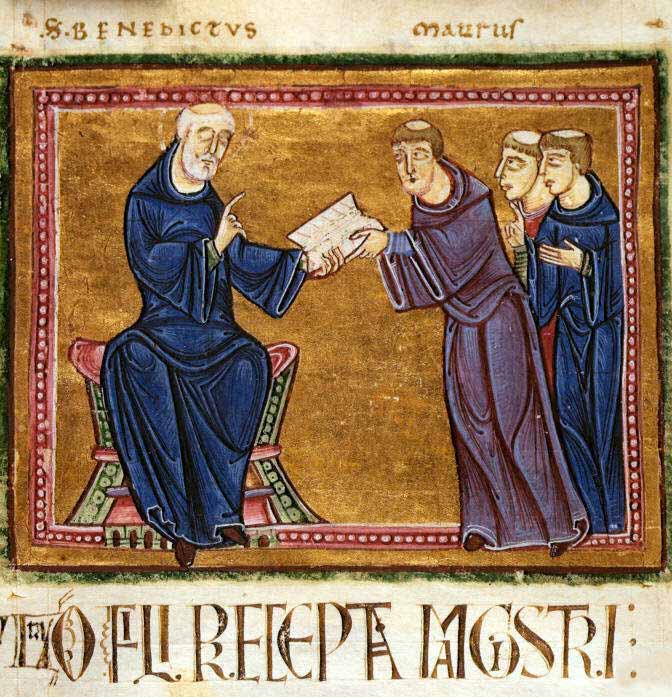

With all the renown he gained by his numerous miracles, the holy man was no less outstanding for the wisdom of his teaching. He wrote a Rule for Monks that was remarkable for its discretion and its clarity of language. Anyone who wishes to know more about his life and character can discover in his Rule exactly was he was like as an abbot, for his life could not have differed from his teaching.

The great modern commentator on the Rule, Anselmo Lentini, OSB, makes the same point rather differently. “The good monk,” he says, “reads and rereads the Rule to find instruction for the soul and comfort for the heart. In it one hears the voice of the wise teacher, the Father, the one who can show him or her how, in the company of many brothers and sisters, to attain the perfect love which casts out fear to seek and find the way home to God.”

Benedict was thoroughly immersed in the two hundred years of monastic tradition that preceded him and reflects it in his Rule. He is clearly dependent on the somewhat earlier Italian Rule of the Master, parts of which he simply adopts but which he generally shortens considerably and always transforms by his own discretion, moderation, and humanity. He makes greater use of Saint Augustine, especially in his treatment of fraternal relations within the community, than he does of the Master. He knows the Egyptian sources, Saint Pachomius, Saint John Cassian, as well as Saint Basil. Other early Latin monastic writings less familiar to the modern reader, such as the Rule of the Four Fathers and the Second Rule of the Fathers, were also known by him.

Saint Benedicts Way of Life – After the Prologue, Benedicts Rule falls into two sections. In chapters 1-7 one finds the core of his spiritual doctrine. This is followed, in chapters 8-73, by regulations for ordering the community’s life of work and prayer and its system of administration. This distinction is not at all absolute, however, as the latter chapters of the Rule are also full of Benedicts own spiritual wisdom and teaching.

Click to read more information: Rule of St. Benedict